Blood glucose is the sugar (glucose) that travels through your bloodstream. It's your body's primary energy source, especially for the brain and muscles.

You can effectively manage your blood sugar levels by choosing foods that contain carbohydrates, like fruits, bread, rice, or milk, and balancing them with other nutrients. This sugar enters your blood and is either used for energy immediately or stored for later, depending on your body's needs.

Your body uses a hormone called insulin to keep everything in balance. This hormone, produced by the pancreas, acts like a key to help glucose move from your blood into your cells. If this system isn't working well—like in diabetes or insulin resistance—blood glucose can stay too high, which may damage tissues and organs over time. Insulin resistance is when the body's cells don't respond well to insulin, leading to high blood sugar levels.

Keeping blood sugar in a healthy range helps you feel steady, focused, and energized throughout the day.

Glycosylation is the process by which sugar molecules (like glucose) attach to proteins or fats in the body. This normal and essential process helps cells function properly, like assisting proteins to fold correctly or sending signals between cells.

But when blood sugar is too high for too long, extra glucose starts sticking to proteins uncontrollably, especially to hemoglobin in red blood cells. This is called non-enzymatic glycosylation, which the A1C test measures.

So, while some glycosylation is necessary and healthy, too much, caused by high blood sugar, can lead to damage over time, especially in blood vessels, nerves, and organs.

Hemoglobin A1C (often called A1C) is a blood measurement that reflects your average blood glucose levels over the past 2 to 3 months. It measures the percentage of your red blood cells that are coated with sugar (glucose). When sugar enters your bloodstream, it sticks to hemoglobin—the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. The more glucose in your blood, the more sugar-covered hemoglobin you'll have, and the higher your A1C result will be. Because red blood cells live for about three months, this test gives a longer-term view of your blood sugar trends, unlike a fingerstick that only shows what's happening at that moment.

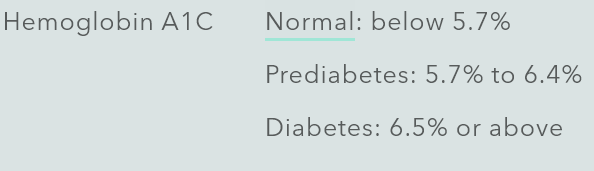

Clinicians use A1C to diagnose prediabetes, diabetes, and to monitor how well someone with diabetes is managing their blood sugar over time. It's reported as a percentage. A result under 5.7% is considered normal, 5.7% to 6.4% is prediabetes, and 6.5% or higher typically indicates diabetes. The goal for most people with diabetes is to keep A1C below 7%. Still, that target can vary depending on age, health status, and personal goals. The beauty of the A1C test is that it isn't affected by daily ups and downs—it gives a broader picture of blood sugar control.

A1C levels rise when blood glucose stays elevated for extended periods. This can happen when the body becomes insulin resistant (where cells don't respond well to insulin) or when the pancreas doesn't produce enough insulin. When insulin isn't working correctly, glucose builds up in the bloodstream instead of moving into cells for energy. Over time, this excess sugar binds to hemoglobin, pushing A1C levels higher. Factors that contribute to rising A1C include a high intake of sugary or refined carbohydrate foods, chronic stress, poor sleep, a sedentary lifestyle, and hormonal changes.

Meet Carla (the name and identifying details have been changed to protect her identity) – A Real-Life Wake-Up Call on A1C

Carla is a 46-year-old mom of two who came to me feeling completely drained. She told me, “I’m tired all the time, I’m gaining weight even though I’m not eating more, and I just don’t feel like myself.”

We ran a few labs, and her A1C came back at 6.8%—officially in the range of Type 2 diabetes. She was shocked. She doesn’t eat a lot of sweets and figured it couldn’t be blood sugar. But we discovered together that her stress, skipped meals, and nightly glass (or two) of wine were quietly spiking her blood glucose throughout the day.

The good news? With just a few key changes—balancing her meals with protein and fiber, managing her caffeine and alcohol, and making sure she actually ate breakfast—we saw her energy bounce back. Three months later, her A1C dropped to 6.2%, and she told me, “I feel like me again.”

A high A1C isn’t a life sentence—it’s a signal. And with the right strategies, your body can absolutely get back on track.

With consistent lifestyle changes that support better insulin sensitivity and more stable blood sugar, you can bring your A1C down. These changes include choosing high-fiber whole foods, regular movement (especially after meals), stress reduction, and balancing meals with healthy fats and proteins. Even a 1% reduction in A1C can dramatically lower the risk of diabetes-related complications, showing that every step you take toward balanced eating and mindful living has real, measurable power.

A1C levels are influenced by the types and amounts of carbohydrates consumed and overall dietary patterns. Foods that quickly raise blood sugar levels include sugary snacks, refined grains, and sweetened beverages. On the other hand, whole foods like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains have a gentler effect on blood sugar levels due to their fiber content, which slows down digestion and reduces the glycemic impact of the meal. Glycemic impact refers to how quickly and how much food raises blood sugar levels. Fiber combined with carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins can synergistically reduce the glycemic effect of a meal. A meal with a balanced combination of carbohydrates, proteins, and healthy fats can lead to slower digestion, improved satiety, and a more stable blood sugar response post-meal. This balanced approach is particularly beneficial for individuals with diabetes or those managing insulin resistance. There are six key strategies to help lower A1C: a balanced food routine, eating fiber-rich foods, eating healthy fats, limiting sugar, including lean protein, and using portion control.

Managing blood sugar levels is essential for anyone with diabetes or those at risk. One of the most important markers to watch? Your A1C. This number gives a snapshot of your average blood sugar levels over the past 2–3 months. While medications certainly have a place, the real magic often lies in your daily choices, especially your food choices.

It is crucial to understand how food can be a powerful tool for supporting healthy blood sugar levels and bringing your A1C down sustainably. Your dietary choices play a significant role in managing your A1C, making it important to make informed decisions about what you eat.

Understanding the Food-A1C Connection

A1C levels rise or fall based on your overall eating pattern, especially the kinds and amounts of carbohydrates you eat. Simple carbs like sugary snacks, white bread, and sweetened drinks cause quick spikes in blood sugar. On the other hand, whole foods—think vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains—digest more slowly thanks to their fiber content, giving your blood sugar a smoother ride.

Even better? Pairing carbs with healthy fats and proteins slows down digestion even more. This leads to a more stable blood sugar response, improved satiety, and less strain on your insulin system. That balance is a key strategy for managing A1C.

Understanding the Impact of Food on A1C

A balanced diet with adequate amounts of healthy fats, lean proteins, and high-fiber carbohydrates helps create a more stable blood sugar response after meals. This balanced approach prevents extreme fluctuations in blood glucose levels and supports more consistent A1C readings. To slow digestion, include lipids (fat) and protein in your snacks and meals. Foods rich in fats take longer to digest than carbohydrates. When consumed with meals, fats can slow the rate at which the stomach empties its contents into the small intestine. This delayed gastric emptying results in a more gradual release of nutrients (including glucose) into the bloodstream, preventing rapid spikes in blood sugar levels. Like fats, proteins also slow down the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates. Proteins are broken down into amino acids during digestion, which are absorbed more gradually in the small intestine than simple sugars derived from carbohydrates. This gradual absorption contributes to a slower and more sustained release of glucose into the bloodstream. Like fats, proteins also slow down the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates. Proteins are broken down into amino acids during digestion, which are absorbed more gradually in the small intestine than simple sugars from carbohydrates. This gradual absorption contributes to a slower and more sustained release of glucose into the bloodstream. Protein digestion requires more energy (calories) than carbohydrates or fats, a process known as the thermic effect of food. This increased energy expenditure can help manage weight and improve overall metabolic health, indirectly supporting better blood sugar control. Protein consumption stimulates a modest insulin response but is generally less pronounced than carbohydrates. The insulin response to protein helps facilitate the uptake of amino acids into cells for protein synthesis and maintenance without causing significant spikes in blood glucose levels. Incorporating adequate amounts of healthy fats and lean proteins into meals can help slow digestion, blunt insulin responses, and contribute to better overall blood sugar management. This dietary strategy supports glycemic control and promotes satiety, weight management, and long-term metabolic health.

Stay tuned... On Wednesday, there will be practical tips to lower A1C.

References:

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Supplement 1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S001

2. Cosme F, Pinto T, Aires A, et al. Red Fruits Composition and Their Health Benefits-A Review. Foods (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;11(5). doi:10.3390/foods11050644

3. Castanys-Muñoz E, Martin MJ, Vazquez E. Building a Beneficial Microbiome from Birth. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):323-330. doi:10.3945/an.115.010694

4. Chang W-L, Chen Y-E, Tseng H-T, Cheng C-F, Wu J-H, Hou Y-C. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Prediabetes. Nutrients. 2024;16(8):1105. doi:10.3390/NU16081105

5. Costantini L, Molinari R, Farinon B, Merendino N. Impact of omega-3 fatty acids on the gut microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12). doi:10.3390/ijms18122645

6. Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731-754. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2337/dci19-0014

7. Franz MJ, MacLeod J, Evert A, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Practice Guideline for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Systematic Review of Evidence for Medical Nutrition Therapy Effectiveness and Recommendations for Integration into the Nutrition Care Process. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):1659-1679. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.06.002

8. Gonçalves B, Pinto T, Aires A, et al. Composition of Nuts and Their Potential Health Benefits-An Overview. Foods (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;12(5). doi:10.3390/FOODS12050942

9. Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Clinical and Translational Report Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake Cell Metabolism Clinical and Translational Report Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Ca. Cell Metab. 2019;30:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

10. Mierzyński R, Poniedziałek-Czajkowska E, Sotowski M, Szydełko-Gorzkowicz M. Nutrition as Prevention Factor of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(11). doi:10.3390/NU13113787

11. Wilson AS, Koller KR, Ramaboli MC, et al. Diet and the Human Gut Microbiome: An International Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(3):723-740. doi:10.1007/S10620-020-06112-W